Stefano Levi Della Torre

tr. Franca Varini and James Wintner

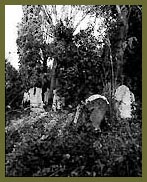

The Jewish cemetery at the Lido di Venezia has

the reserve of a fenced wood and, at the same time, the enduring quality typical of an

archaeological site. It is a characteristic common to other Jewish cemeteries in Italy and

in Europe, where the alternation of care and abandonment over the span of many centuries,

reflects the historical record -- bad and good -- of their communities. The gravestones emerge from a

sea of overgrown grass, inclined or flat, or leaning against the brick wall, in the shadow

of trees that have grown wild: some have grown so as to embrace the edge of a stone or to

have split it. We find not only the funereal cypresses, but plants of many species,

casually or intentionally left as a sign of life (Bet ha-Khaiim, “house of the

living” is, in Hebrew, the euphemism which designates the cemetery). The light of the

lagoon filters through the leaves. Traces of an order -- a garden, efforts of an earlier

age -- are now confused by the wild vegetation, and the half-submerged tombs recall a

return to the earth, leaving on the surface a residue of white stone -- a silent disorder

-- or, on the contrary, a re-emergence of memory. gravestones emerge from a

sea of overgrown grass, inclined or flat, or leaning against the brick wall, in the shadow

of trees that have grown wild: some have grown so as to embrace the edge of a stone or to

have split it. We find not only the funereal cypresses, but plants of many species,

casually or intentionally left as a sign of life (Bet ha-Khaiim, “house of the

living” is, in Hebrew, the euphemism which designates the cemetery). The light of the

lagoon filters through the leaves. Traces of an order -- a garden, efforts of an earlier

age -- are now confused by the wild vegetation, and the half-submerged tombs recall a

return to the earth, leaving on the surface a residue of white stone -- a silent disorder

-- or, on the contrary, a re-emergence of memory.

The

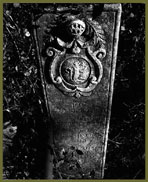

photographs of Claire Turyn convey this sense of a memory alternating between the enduring

and the impermanent. Up close, the blotches of shadow and light obscure the carved

inscriptions and decorations; the erosions of water and sea air, and the lichen stains,

intertwine with the inscriptions like another inscription superimposed on the original.

From a distance, the monuments of chalk-white Istrian stones appear like apparitions in

the middle of the forest, vivid signposts in the indifferent vegetation. The

photographs of Claire Turyn convey this sense of a memory alternating between the enduring

and the impermanent. Up close, the blotches of shadow and light obscure the carved

inscriptions and decorations; the erosions of water and sea air, and the lichen stains,

intertwine with the inscriptions like another inscription superimposed on the original.

From a distance, the monuments of chalk-white Istrian stones appear like apparitions in

the middle of the forest, vivid signposts in the indifferent vegetation.

The cemetery grounds have their origins in a vineyard adjacent to the

Benedictine monastery of San Nicolo di Mira. It was given to the Jews in perpetuity for

the purpose of burial in 1386, in a period when the relationship between the Jews and the

Serenissima was becoming more organic and formalized. (In fact, one year earlier, 1385, the candotta de banco

, banking license, was granted to certain Jewish families in Mestre.) formalized. (In fact, one year earlier, 1385, the candotta de banco

, banking license, was granted to certain Jewish families in Mestre.)

The Jewish community on the lagoon, documented since the 11th century,

developed through highs and lows, restrictions and concessions. The increasing dominance

of Venice throughout the Mediterranean and beyond, both economically and politically, made

it a magnet for immigration. Jews from all over Europe and the Mediterranean flocked

there. Religious and social tensions arose. In 1516 the Senate created the ghetto in

Cannaregio:

“siano (gli ebrei) tenutj et debino andar immediate ad habitar unidj in la corte di

case che sono in geto apresso San Hieronymo: loco capacisimo per sua habitacione.”

(The geto, from which it is believed the word “ghetto”

derives, was a foundry zone -- getto (jet) of copper. . .). Jews were gathered and

segregated there. They were initially seven hundred in number, but their population in

Venice kept growing, reaching a maximum of five thousand (out of a total population of one

hundred fifty thousand) around 1630, immediately before the Plague. (In the cemetery there

is a communal grave, recalling the Plague, with the inscription “Hebrei 1631.”)

Living together in the ghetto were the many Jewish “nations”: Italians,

as well as those coming from other regions of Europe and of the Mediterranean; the

Ashkenazi from Germany, Poland, or Russia; the Sephardim expelled from the Iberian

Peninsula; Westerners; Easterners; etc. Each nation had its own rituals and synagogue, but

all were joined as Jews and as Venetians.

Later on, the Jewish population began to decline in number and economic

force, pushed down little by little, like many other minorities subject to the

Serenissima, by restrictions and prohibitions.

This evolution is reflected in the history of the cemetery, first in its expansion and its

decoration, then in its decline. Towards the end of the 1700s it stands abandoned on an

almost deserted island. The sand accumulates, carried by the winds. The wild vegetation

invades and covers the cemetery grounds. The solitude of this place, expected perhaps, for

it was isolated like a ghetto of the dead, did not guarantee its tranquillity: situated on

the strip of land between sea and lagoon, at a strategic opening of the harbor, the

cemetery has endured (starting in the 1600s) successive works of fortification.

This evolution is reflected in the history of the cemetery, first in its expansion and its

decoration, then in its decline. Towards the end of the 1700s it stands abandoned on an

almost deserted island. The sand accumulates, carried by the winds. The wild vegetation

invades and covers the cemetery grounds. The solitude of this place, expected perhaps, for

it was isolated like a ghetto of the dead, did not guarantee its tranquillity: situated on

the strip of land between sea and lagoon, at a strategic opening of the harbor, the

cemetery has endured (starting in the 1600s) successive works of fortification.

When, during the course of the 19th century, a new cemetery was opened

in an adjacent area, and the Lido was urbanized, the excavations revealed many graves long

hidden from sight. The tombstones are reunited on a small site in the old cemetery, once

again enclosed. Many stones have lost their original place, and the many Jewish

“nations,” once distinct, now find themselves strewn together in the entrance

area (originally reserved for the Sephardim) facing towards Venice. On that shore landed

the funeral gondolas of the Hevrat Ghemilut Hassad’m, the Jewish burial

society. Leaving from the ghetto, the cortege of boats traversed the lagoon, taking a

route which avoided passages and bridges from which someone could have thrown objects and

trash in mockery of the Jews.

The photographs of Claire Turyn testify to this tranquil ruin, this

mixture of “nations.” Groups of stones in their disarray sway back and forth as

if in ritual oscillation; grassy fissures traverse the stones; carved figures reject a

too-rigid interpretation of the prohibition against images (“Thou shalt not make unto

thee a graven image...” Deut. 5). In fact, the gravestones are covered with sculpted

images, particularly beginning in the late 1500s, the imagery a mix of Hebrew and Venetian

references.

There is the Lion of San Marco -- perhaps the one of Judah: “Judah

is a lion’s whelp;/ On prey, my son, have you grown./ He crouches, lies down like a

lion,/ Like the king of beasts -- who dare rouse him?” (Gen. 49:9).

(Perhaps deriving from San Marco is the family name of emigrants to Germany: Marx). In a

vortex of ivy appears a

siren, half woman, half creature of the sea, again a possible allusion to Venice. There

are Baroque volutes, which frame Hebrew inscriptions, and there is a large gravestone of a

Dutch Sephardic Jew with stone drapery held by small putti. Here we see a plumed helmet of

the Spanish Hidalgos, not in memory of the Sephardic Jews’ warrior past, but, rather,

nostalgia for the respect and lost protection of a land from which we were expelled. There

is the imperial eagle with two heads, perhaps an homage to an empire whose pluralistic

dominion had granted less confining living conditions to the Jews. ivy appears a

siren, half woman, half creature of the sea, again a possible allusion to Venice. There

are Baroque volutes, which frame Hebrew inscriptions, and there is a large gravestone of a

Dutch Sephardic Jew with stone drapery held by small putti. Here we see a plumed helmet of

the Spanish Hidalgos, not in memory of the Sephardic Jews’ warrior past, but, rather,

nostalgia for the respect and lost protection of a land from which we were expelled. There

is the imperial eagle with two heads, perhaps an homage to an empire whose pluralistic

dominion had granted less confining living conditions to the Jews.

But more common are the symbols, or Rebuses, more specifically Jewish:

the stele divided into two vertical bands ending with two lobes at the top, like the

“Tablets of the Law,” refer to a married couple. The deer in the basket, in one

interpretation an allusion to Moses saved from the waters of the Nile (or perhaps from the

lagoon?) is a symbol of the Serravalle. The moon, the stars, and the cock, sometimes with

a palm branch clutched in its claws, is from the Luzzatto family of ancient Ashkenazi

derivation. The hands in benediction with the fingers joined two by two and the thumbs

extended out (the three parts of the benediction) above the crown (the Torah, the

Scriptures) represent the Kohane, the high priests.

The pitcher which pours the water into the bucket for the ritual

cleansing is from Levi, being the Levites, the ancient tribe assigned to the cult. The

ladder, similar to the one in the dream of Jacob (Gen. 28:12-15) belongs to the Sullam

(which in Hebrew means ladder). The scorpion, which in truth looks like a spike, is from

the family Copio (scorpio). The moon is Lunuel di Francia (of France) o Jarach (jar*akh

means “moon” in Hebrew), while the moon inside the sun belongs to the Habib.

Here is the tree of life rising from a vase or from a mountain. The crenelated tower which

has at its top the figure of a woman holding a sword in one hand and a palm branch in the

other, is in praise of woman, who is fortress and peace according to the last chapter (31)

of the Biblical Book of Proverbs: “A woman of valour who can find? For her price is

far above rubies . . . Strength and dignity are her clothing; And she laugheth at the time

to come.”

Here is the tree of life rising from a vase or from a mountain. The crenelated tower which

has at its top the figure of a woman holding a sword in one hand and a palm branch in the

other, is in praise of woman, who is fortress and peace according to the last chapter (31)

of the Biblical Book of Proverbs: “A woman of valour who can find? For her price is

far above rubies . . . Strength and dignity are her clothing; And she laugheth at the time

to come.”

The wall of large ashlar surmounted by columns invokes the memory of

the Kotel ha-ma’rav, the Western Wailing Wall, remnant of the Temple of Jerusalem

destroyed by the Emperor Titus in 70 A.D., but it is not only a memory, it is also the

aspiration to return to the promised land. Many in their old age went there to die, others

left as their final wish the desire to be buried there, and a legendary hope was that the

dead would in any case reach the land of Israel through subterranean paths, in order to be

there on the day of resurrection.

Among the illustrious graves there is the one of the Rabbi Leone da

Modena, a great teacher and writer, but addicted to gambling, who died in poverty in 1648.

His funeral was paid by the Hebrew “University” and his modest stone is, like

many others, a fragment of a window sill in Masegna stone: in the back we see the

mouldings, on the front we read the inscription made by Leone himself: “Words of the

dead. Four arms’ length of land in this enclosure, possessed for eternity were

acquired from above for Giuda Leone da Modena. Be gentle with him and give him

peace.” There is the gravestone of Elia Levita, grammarian of the 16th century; and

the one of Sara Copic Sullam, poet and the guiding spirit of a literary salon in the first

half of the 17th century:

This is the stone of the distinguished

Signora Sara (. . .) woman of great genius

wise among the wives

supporter of the needy

the unfortunate found in her a companion

. . . On the predestined day God will say: come back,

come back o Sulamita

Here, with a play of words, reference is made to the surname

“Sullam” and to Sulamita, the beloved of the Cantico dei Cantici . But these

tombs are modest, without any particular distinction, mixed in with the other stones.

In the variation of styles across time we read the relationship between

the Jews and Venice: changes of fashion -- the sober classicism of the Renaissance, the

excesses of the Baroque -- reflect the level of intimacy with “gentile” society.

In the ghetto the synagogues from many eras are adorned with the finest that Venetian

artisans could offer in the decorative arts.

The oldest stones are severe, characterized essentially by their

inscriptions. Between the 1500s and 1600s there was an increase in the volutes and in the

figurative puzzles (Rebuses) which we have already described. In the 1600s and especially

the 1700s sarcophagi appear, such as the one captured by Turyn with the large open mouth,

or the one in the new cemetery, marble covered by a high relief brocade.

In the 19th century, and thus in the new cemetery (which is still in

use), the sepulchers start to resemble those of a Christian cemetery, seen in their

similar monumental elements. By then the Biblical prohibition against the use of images is

completely ignored --- portraits of the dead in low or full relief, in photographs and

sometimes in mosaics like in the sepulcher of the Jesurum, decorated by lace carved in

stone, celebrating what the family had done in the production and international trade of

Burano lace. Not only the styles, but even the symbols borrow from those of the Gentile

cemeteries of the same period: the urns veiled with marble drapery, the obelisks, the

broken columns for premature deaths, the sculpted funeral wreaths, even the chapels. These

forms represent the progressive social and economic assimilation of many Jews after the

emancipation. At the same time in Turin, Florence, and Rome, the grand synagogues of a

united Italy were being erected as if they were “Jewish churches” with only a

Moorish or Babylonian touch connoting a “difference” just a touch exotic.

Today, through the eyes of someone who has lived through or who knows

the tragedy of the Jews in the 20th century, these “assimilated” and pathetically optimistic

tombs stand now as testament to an illusion: that with the emancipation of the 18th

century the tragedies of the Jewish people had come to an end. This, of course, was not to

be. And thus in recent decades we have seen a return to the ancient sobriety: the tombs of

the last decades are bare stones marked only with inscriptions. in the 20th century, these “assimilated” and pathetically optimistic

tombs stand now as testament to an illusion: that with the emancipation of the 18th

century the tragedies of the Jewish people had come to an end. This, of course, was not to

be. And thus in recent decades we have seen a return to the ancient sobriety: the tombs of

the last decades are bare stones marked only with inscriptions.

The photographs of Claire Turyn linger especially on the ancient

cemetery, with a glance towards the new: they are enigmatic portraits, traces of many

different stories that are yet to be completely understood.

Milan, 1997

The photographs referred to in this essay, and the essay itself, can be viewed

on PhotoArts.

See also, “A Little String Game,” Vol. 1, No.

2

_____________________________________

©Claire Turyn, photographs; Italian text Stefano Levi Della Torre; translation, PhotoArts. From

“The Jewish Cemetary at the Lido, Photographs by Claire Turyn,” with permission

of PhotoArts (http://photoarts.com).

next page |