|

l i v i n g w i t h g u n s |

m a r y - s h e r m a n w i l l i s |

|

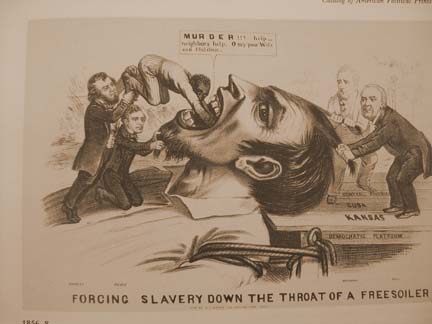

Among my family’s books and letters are some first-person accounts of the Kansas-Missouri Border War, a prelude to the Civil War, writ small and concentrated. Published here for the first time, are letters from the scene in Kansas in May, 1856, by my great-great-grandmother Cecilia Stewart Sherman, when the violence flashed into what she herself called a “civil war.” Along with the letters, the two-volume biography of her husband, John Sherman, William Tecumseh’s younger brother and my great-great-grandfather, includes his account of events. Cecilia’s urgent descriptions are balanced by John’s more reflective voice — he was writing almost forty years after the events and knew exactly where they led. Taken together they are extraordinarily revealing about an American buildup to war. One hundred-and-fifty years ago, Kansas was contested territory, the fight a mixture of doctrine and greed, fueled by widespread gun-ownership and by ineffective law enforcement. Until then the Kansas Territory had been the pass-through route to the Golden West or south to Mexico. The Territory itself belonged to the Otoes, Ioways, and Missouria; the Kickapoos, the Kaskaskias, Peorias, Shawnees, Delawares, Wyandottes, Chipewas, Osages, and Pottawatomies — Native American tribes already in decline, their names left as markers. Settlers kept to the trails etched into the prairies, the Santa Fe Trail heading south, or the California Trail through the Donner Pass on the way to the riches beyond. They rarely stopped to stay; the open space oppressed them. They felt vulnerable. But that trend changed in 1854 with the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which meant the repeal of the Missouri Compromise of 1820 that strictly limited the number of new slave states to be admitted to the Union. Now, the Act determined that each new state could decide on slavery for itself, by popular vote. It also included the Fugitive Slave Act, which implied that no state was free, because a slave was always a slave, even in a state where slavery was banned. The formal issues during the Border Wars were slavery and the rights of states, but informally, the conflict was all about property. Missouri, which had been a prosperous slave state since 1821, determined to see to it that its new neighbor to the west would, likewise, be a slave state. Missouri slave property — human beings — was at stake, valued then at $150 million. With no clear guidance from distant Washington, people took matters into their own hands. Missourians and Southern sympathizers moved into the Territory to create a pro-slavery presence, while abolitionist settlers from New England and Illinois and Ohio took the long trip West to keep Kansas soil slave-free. Back in Washington, Southern and Northern interests wrestling for control of the Congress saw Kansas as a proving ground for or against slavery. Democrats represented the South and the expansion of its peculiar institution. On the opposing side, the Republican Party rose from the ashes of the Whig Party in 1854. Its platform was to end slavery and to keep the Union whole. The fight would become violent even within the Capitol. Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, a founder of the Republican party, was beaten unconscious with a cane on the Senate floor in May of 1856 by Rep. Preston Brooks of South Carolina for besmirching the name of Brook’s uncle, another South Carolina congressman, in an anti-slavery speech. Afterwards, Brooks triumphantly brandished his cane throughout the South, while Sumner’s bloody shirt was paraded throughout New England. As skirmishes intensified between pro- and anti-slavery forces, several important Civil War figures got a taste for the fight in the Kansas Territories. Lt. Col. Robert E. Lee and Lt. J.E.B. Stuart, U.S. Army veterans of the Mexican War, both were stationed in Fort Leavenworth and had run-ins with the abolitionist guerrilla John Brown, whose militia would murder five men in cold blood in Osawatomie, Kansas, in May of 1856. Three years later, it would be Lee’s job to bring Brown to justice for trying to incite a slave revolt in Harper’s Ferry, Virginia — a final act of terrorism for which Brown was hanged. Another Mexican war veteran, William T. Sherman, came to Leavenworth in 1858, to try his hand at law with his Ewing brothers-in-law, who had allied themselves with the Free-State Party. He had no law license, but a local judge allowed him to practice “on the grounds of general intelligence.” Even so, he failed as a lawyer and spent the winter writing impassioned letters on the Union and the “slavery question” to his brother John in Washington, D.C. Also back from the Mexican war, Ulysses S Grant was a farmer in Missouri; Abraham Lincoln in Illinois was an early denunciator of the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Samuel Pomeroy was an anti-slavery fighter from Massachusetts in search of a political career, who would be sent to the U.S. Senate in 1861 when Kansas became a state. On the other side, Samuel D. Lecompte, the first chief justice of the Territorial Supreme Court, ruled against the Free Soilers in 1856, calling them traitors; the pro-slavery town of Lecompton was named for him. In 1856, John and Cecilia Sherman had been married eight years and were childless. He was thirty-three years old; she was twenty-seven. The couple was in their first year of living in Washington, D.C., having come from Mansfield, Ohio, Cecilia’s home town, where John had worked as a lawyer with his older brother Charles. There he had dabbled in Whig politics, but the repeal of the Missouri Compromise had motivated him to run for office; in 1854 he was elected as a Republican to the U.S. House of Representatives. Cecilia was a “carefully educated” woman, according to John, and an intelligent and supportive partner in his long political career, which would include a term as a Congressman, consistent re-election for forty years to the U.S. Senate, and service as Secretary of the Treasury under Rutherford B. Hayes, and as Secretary of State for William McKinley. The Sherman Anti-trust Act is named for him. Cecilia was known in Washington for her propriety and correctness. As a couple they were never considered warm; John, in fact was thought to be so humorless he was nicknamed the Human Icicle. But the passion Cecilia voices in her letters gives an idea of the heat that the Kansas conflict generated at the time. The press had done much to fan the flames. The vote to elect a Kansas Territorial legislature was scheduled for March of 1855. Pro-slavery firebrands like hard-drinking David Atchison and John Stringfellow exhorted their supporters in the Atchison (Kan.) Squatter Herald, the so-called Border Ruffians, to cross into Kansas and vote, by force if necessary. Stringfellow’s brother Ben wrote, “To those who have qualms of conscience as to violating laws, state or national, the crisis has arrived when such impositions must be disregarded, as your rights and property are in danger, and I advise one and all to…vote at the point of the bowie-knife and the revolver… I tell you to mark every scoundrel among you that is in the least tainted with free-soilism or abolitionism and exterminate him.” Indeed, thousands of votes were cast. A pro-slavery legislature was established in 1855; it immediately enacted drastic slave codes providing severe penalties for antislavery agitation and authorizing a test oath for officeholders. President Franklin Pierce sent Wilson Shannon, a U.S. congressman from Ohio, to Leavenworth as territorial governor, replacing Andrew Reeder. Pierce, a Democrat, expected Shannon to be pliant to Southern interests. Horace Greeley rallied to the cause in his New York Tribune, summarizing the issue this way: “The contest already takes the form of the People against Tyranny and Slavery.” Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote that he knew people “who are making haste to reduce their expenses and pay their debts, not with a view to new accumulations, but in preparation to save and earn for the benefit of Kansas emigrants.” Political cartoons drove the point home, such as this one in Harper’s:

“FORCING SLAVERY DOWN THE THROAT OF A FREE-SOILER” (Library of Congress Rare Book and Special Collection Division, the Stern Collection) Anti-slavery forces declared the Territorial Legislature a fraud and the election rigged. The New England Emigrant Aid Society in Massachusetts organized colonies of abolitionists to settle in Kansas. Over one thousand made the arduous trip, by train to St. Louis, then by boat down the Missouri River to territorial border, where the Missouri forks into the Kansas River. They headed for Lawrence, which had been established in 1854 about forty miles upriver from the border on the banks of the Kansas. Within a year their tent settlement was replaced by huts and cabins; the town’s most imposing structure, the Society’s Free State Hotel, was built of stone. The Society’s agent, Dr. Charles Robinson, and his wife Sara would become the organizing center of the anti-slavery forces. Though Robinson advocated non-violent resistance to the elected legislature, the Society had the foresight to equip the colonists with sixty of the latest in rifle technology: the fearsome Sharps breech-loading rifle, manufactured by its inventor Christian Sharps in Philadelphia. Easy to load and deadly accurate, it was dubbed the “Beecher’s Bible” for the New York minister who advocated its use in what was deemed a holy war to end slavery. (During the Civil War, companies armed with Sharps rifles were known as sharpshooters.) Mere rumor of these arms kept the Missouri Border Ruffians at bay. The town of Lawrence bought some time to become established. Partisan newspapers kept tallies of the atrocities perpetrated by each side and exhorted their supporters to action. Offended readers often stormed the presses and threw them in the nearest river. The New York Tribune reported of the axe murder of free-soiler Reese Brown by whiskey-crazed Ruffians. “One of the wretches...stooped over the prostrate man, and, with a refinement of cruelty exceeding the rudest savage, spit tobacco juice in his eyes.” The Lawrence Herald of Freedom described the tar-and-feathering of free-soil lawyer William Phillips in Leavenworth: he was paraded through the streets and then “sold” by a Negro for a dollar before being thrown into the Missouri. Unchastened by the violence, pro-slavery agitator David Atkinson’s Squatter Sovereign threatened to “continue to lynch and hang, to tar and feather, and drown every white-livered abolitionist who dates to pollute our soil.” Law enforcement was often compromised. For instance, Indian agent George Clarke was accused of leading an ambush that killed Thomas Barber, one of a group of abolitionist settlers returning to their farms from Lawrence to cut firewood. “I have sent another of these damned abolitionists to his winter-quarters,” said Clarke, according to a news report from Sara Robinson. Sara also reported how Missouri sheriff Sam J. Jones was the leader of an armed “motley gang” of ballot stuffers from Westport, who tried to force their way into the cabin that served as a poll. When unsuccessful, “[a] pry was then put under the corner of the log cabin, letting it rise and fall…. The two judges still remaining firm in their refusal to allow them to vote, Jones led on a party with bowie-knives drawn, and pistols cocked. With watch in hand, he declared to the judges, ‘he would give them five minutes in with to resign, or die….’” U.S. Marshall Israel Donelson was equally partisan. It was he who led a posse of Border Ruffians intending to destroy Lawrence in May of 1856. With such bias at the highest level of law enforcement, Col. Edwin Sumner, Lee and Stuart’s commander at Fort Leavenworth, was left to issue Federal protection to abolitionist and pro-slavery agitators alike. An impossible task: Missourians were determined to wipe Lawrence and its inhabitants off the map. In December of 1855, Dr. Charles Robinson was made commanding general of the Free State Militia to defend Lawrence against an armed posse of Missourians camped outside the city. Governor Shannon had been unable to control them. Although Robinson had sworn his men to non-violence, they had loaded their Sharps rifles and a smuggled howitzer and were armed to fight, in no small measure helped by the gunpowder their women had cached under their skirts from outlying storehouses. The position of the town — at the edge of the Kansas River in the middle of a plain, flanked by an overlook — made it impossible to defend. But the Ruffians’ knowledge of the inhabitants’ weapons — and a sudden winter storm with sleet and gale force winds — had kept attackers at bay. The only casualties that time had been a pro-slavery fighter who had shot himself in the foot, another felled by a fallen tree, another killed by his own sentry, and a fourth killed in a barroom brawl. The attackers would wait until spring to make their next assault. Meanwhile, word of the election fraud and the siege of Lawrence was telegraphed back to Washington. In January of 1856, President Pierce sent a worried message to the House about the situation in Kansas and asked that money be set aside for the “maintenance of public order in the Territory of Kansas.” In March the House decided to assemble a committee to see the situation first hand, take testimony from both sides, and get an account of the territorial election. The committee would consist of three congressmen: Mordecai Oliver of Missouri; John Sherman of Ohio; and Chairman William A. Howard of Michigan. Accompanying them were a stenographer and a guard. They would travel by train to St. Louis, arriving April 12th, then continue by steamer and over land, taking testimony at both free-soil and pro-slavery settlements. They then would return the way they came, arriving in Detroit by June 17th to compile the report formally. John Sherman picks up the story here:

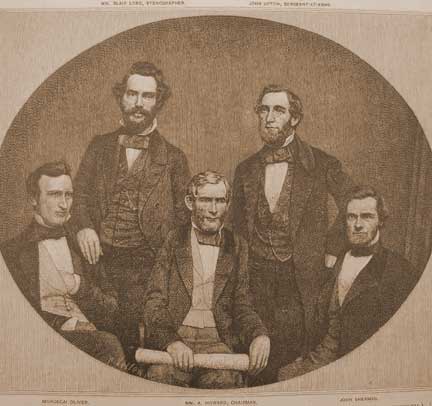

Kansas Investigating Committee, from left to right: Mordecai Oliver, Commissioner (Missouri); W. Blair Lord, Stenographer; William A. Howard, Chairman (Michigan); John Upton, Sergeant-at-arms; John Sherman, Commissioner (Ohio). The print of the investigative committee is credited to the Kansas Historical Society, but there is a copy in John Sherman's book. Also, the records note that it appeared in Century Magazine in 1887. –M-S.W. (LOC Prints and Photographs Division)

Cecilia Sherman in 1897This photo of Cecilia was taken three years before her death by society photographer Frances Benjamin Johnson for the New York Times Sunday supplement on cabinet members’ wives (John was Secretary of State). Its caption: “first portrait taken in 27 years.” I have no earlier image of her, but I do have a copy of a photo from the same group, of her decked out in ermine.—M-S.W. (LOC Prints and Photographs Division)

Cecilia writes to her sister-in-law Fanny, who is in Mansfield, Ohio. John’s younger sister, Fanny was married to Charles Moulton, a prominent Cincinnati lawyer and businessman who looked after John’s political interests in that Democratic city. Leavenworth K.T. May 19th 1856 My dear Fanny, I received Mr. Moulton’s letter a few days before leaving Lawrence for which I am much obliged although I was sorry you were too unwell to write yourself. Mr. Moulton makes a good secretary though and we should be glad to hear more lengthily from him when his time permits. Mr. Sherman has not until yesterday written a letter to anyone since he came into the Territory. He thought it was doubtful if they would get through if he did unless sent by private conveyance to St. Louis. Intercepting of letters is one among the many annoyances the Free State people here have to bear. They cannot get a telegraph through either. The lines are generally down when they want to send or something of the kind. I presume in this the stopping of [Dr. Charles] Robinson at Lexington without any process or indictment, or without one having been found against him & all the other outrages committed daily, together with the army collected from Missouri Ruffians for the declared purpose of killing or chasing every Free State man from the Territory, has all reached Mansfield. But yet it is impossible for any one so far removed from such scenes to realize them as those who hear and witness them here do. I would say too, it is impossible for them to even believe the half. I do not believe a day has passed since we have been in the territory that some outrage has not been committed upon some Free State man which would make the blood of every northern man boil. If they had only arms, they would not have submitted as passively to insult & oppression as they have heretofore done. Every day for two weeks large bodies of armed men from Missouri have been coming across the river into Kansas at different points. Yesterday there were between one and two hundred from Platte City and Weston Mo encamped on the banks of the Stanger [River] waiting for it to fall so they could ford. [David] Atchison was with them They had two brass cannons, rifles, revolvers & plenty of bowie knives.

…Mr. Jesse Newell, formerly from near Olivesburg & immediately from Iowa with his two sons & a son-in-law, is looking through the county for a location. He arrived [in Leavenworth] today and gave us an account of his adventures for the last two or three days. He was stopped several times before he got through. He was going from Topeka to Lawrence on Saturday but after having been stopped once or twice he turned around and went to Lecompton, the headquarters of the enemy, to see Gov. Shannon whom he knew. He spied him in a crowd upon the street and accosted him thus: “I would like to know what these bands of armed men who are going round the country mean stopping peaceable citizens on the high way—&c &c. I am a free man & thought I was in a free country till I came here,” he said. Shannon got angry & told him there was no use in his getting mad—&c—that the whole Territory was under military law. He then turned to go into his office. Mr. Newell called to him, “Shannon it’s me[,] and you are not going to treat me thus. I’ll know what these things mean.” Shannon then told him to follow him in. He did so & he gave him a permit to pass unmolested through the territory. He then started again for Lawrence but was stopped twice by one party of ten—-& another of fifteen armed with rifles & fixed bayonets; they questioned as to where he was from, when he came, what town he had been, were he was going. He told them, and they said he had been travelling in d—d abolition towns all the time. They supposed he was going now to Lawrence to help fight the Border Ruffians, and he couldn’t go. He told them he had started for Lawrence, there he intended to go. They told him they would take his mules for the use of the army. Says he, “These mules cost eleven dollars & before you get them you’ll take my scalp. He showed them his permit then & they let him go, but Shannon & they too told him there was no use to go, that he wouldn’t get into the town, it was guarded & in arms. But he said he went on & when he came near the town he saw men planting corn & women in the garden. He went on down town & there were little girls jumping the rope, stores were open, the men at their usual work & all was quiet. He didn’t know what to make of it after the stories Shannon had told him about the citizens of Lawrence all being in arms &c. No doubt Shannon thinks they are. The pro-slavery tell him so in order to bend him to their measures & he never goes out of Lecompton so he can find out himself.

[Leavenworth] May 20th A message from Lawrence arrived this morning to communicate the intelligence of more outrages committed upon their men there. Their horses are stolen from them and everything else [that] this army of ruffians denominating themselves [as] Marshall Donaldson’s [sic: U.S. Marshal Israel Donelson] deputies can convert to their use. One old man was plowing with six yoke of oxen. They came & took from him three of the yokes—if they say anything against their proceedings they will knock them down as if they were dogs & they are such cowards they will never make the attack except when they are three to one; thus the free state men have no chance to defend themselves. Yesterday about two o’clock a young man by name of Stewart from Ashtabula Co. Ohio was in a grocery a few miles from Lawrence when two or three or four of the Ruffians came in & walking up to him said, “We are going to search your pockets.” Stewart says, “I guess you are not.” & put himself in an attitude of defense. [A] young man in the grocery handed him a pistol saying, “Here, defend yourself.” Whereupon the fiends leveled their guns at him telling him, “We will shoot you if you do not lay down that pistol.” Stewart laid it down and got on his horse & was riding off when one of them said to the others, “D—n it, let us shoot him anyhow.” & fired a ball passing in at his back and out at his breast. When the news got to Lawrence it produced terrible excitement. They all felt like laying aside their non-resistance plan & flying to arms. Some of his comrades did start for the scene of the murder, and before they got there, one of them was shot through the head & instantly killed. This was at five or six, the same evening one of the Delaware Indians was shot on the other side of the river by a party of the murderers. They hastened over to Lawrence to try to get assistance to protect themselves or revenge the death of one of their tribe. Thus it goes. We know not what to look for next, for these hounds are thirsting for the blood of the Free State Men, but the non-resistance plan rather disarms them. They want to keep the shadow of law on their side and therefore they want to drive them from the position they have taken, and excite them to resistance by aggression and murder. [The Free State men] have proposed to them that if they would let [U.S. Colonel Edwin] Sumner station some of his troops among them to protect them, [the Ruffians] would deliver up all, even their private arms so long as [the soldiers] staid & they might arrest any of their men they chose provided they, the men quoted, were to be protected from the mob. But that when the troops left, their arms must be returned to them again. The reply from Shannon (or Donaldson [sic-Donelson], rather) was that their arms must be delivered into his—Donaldson’s—hands, and not only that, but the two printing presses in the town must be destroyed. They said nothing less would suit Carolinians. Of course the Lawrence people will not submit to such unjust demands. If they had they would only have imposed some other conditions with which they could not comply. They have sworn they are going to kill every man in Lawrence & the women they reserve for a worse fate. If it was not that the Federal Government is on the side of these men, the Free State people would soon show them who is the strongest. But as soon as they would do that, Shannon would call out the U.S. troops and they would be treated as rebels against the U.S. Notwithstanding all this awe of the Federal government, it is very hard for the leaders of the Free State party to restrain their men from pitching in & they say if these outrages continue they will not be able much longer to prevent them.

[Leavenworth,] Wednesday morning. I have written you the war news so far, or some of them, for it would cover many sheets to give you all. And now I will give you a little history of ourselves. The committee finished their duties at Lawrence and that portion of the territory the first of last week. We had been anticipating an attack upon the town for three days and nights before we left, for they had been heard to tell they were going to destroy the testimony in some way or other, and they knew Tuesday was the day set for leaving for Leavenworth—(Oliver & all his party had left on the day previous). As they did not attack the town we did not know but their plan was to attack us on our way to L.

A good portion of the original testimony had been sent on to Washington by Gov. Robinson (when he was taken of the boat at Lexington in such a dastardly manner his wife went on with it). The rest I sewed up in pockets made on the inside of my quilted skirt, the copies the sergeants at arms took charge of. Mr. Sherman & I started ahead of the rest. It was understood that he carried the testimony —when we got across the river Sergeant Dufries of the USA inquired of Mr. Sherman if he was the gentleman going to Leavenworth. He answered he was and [Dufries] said he would accompany us. Whether this meeting was accidental or whether he had been secretly instructed by Col. Sumner who had been at Lecompton on Saturday we don’t know. We came through without molestation. The road from Lawrence here lies through the Delaware Reservation and it is the most beautiful country one can imagine. I thought what I had formerly seen of the territory was as fine as it could be, but this surpasses it. There are thousands & thousands of acres, miles in extent, upon which you see no habitation, and often no living things but birds. I think one has a deeper sense of loneliness or solitude on these great uninhabited prairies than we would feel in dense forests of the same extent. I think probably the prairies are more beautiful now, crowded as they are with the fresh green grass and such a variety of wild flowers, than they are when the grass is taller. It grows they say nearly as tall as a man’s head. Leavenworth is much better built than Lawrence and is still more beautifully situated than it. We are boarding at a private home, Mr. Keller’s. He formerly kept the hotel. At the time Phillips was tarred and cottoned, when [Keller] found some of his boarders was engaged in that affair, he told then to walk up to the desk, settle their bills & leave his house. He would have no one about him who had been engaged in such a cruel dirty affair. He was born and raised in Kentucky, lived in Missouri for seventeen years before he came here and was with the pro-slavery party, till he says he became so disgusted he couldn’t go with them any longer. Many others have told us the same thing…. On the Thursday after I came here, Mrs. Sumner and her daughters came to see me and invited us to come on Sabbath morning & witness the grand cavalry parade. We went but unfortunately were a little too late. It was nearly over. There were about five hundred on parade all in full dress uniform. The grandest sight I ever saw in America. I once witnessed a parade of British cavalry at Montreal. There are a great many handsome young officers at Fort L. Mary [Sherman]1 would be in her element here, and have a much better field for the exercise of her powers of captivation than Washington. They have four brides there now. About twenty of the officers have wives with them & having not much to do, there is a great deal of gaiety. They urged us to come & spend some time with them but the committee will spend no time in play. They have worked about 10 hours a day ever since they commenced their duties and are almost worn out.

The Fort is about 2 miles from the city—a military road all the way and a delightful ride. The government farm contains 3,000 acres & is under fine cultivation. The Fort is beautifully located on a high commanding point overlooking the country & river for a great distance. The residences of the officers are handsome. They live on the best Uncle Sam can provide too. Mr. Moore, a young lawyer here, took me all around the government farm yesterday, and up to the top of Pilot Knob, a very high and narrow ridge of rock & of limestone formation, from which we can view the country for miles. The cemetery is on the top of this hill, here the murdered [Reese] Brown is buried—(he was chopped to pieces with lathing hatchets). All who have seen Iowa say Kansas is a much finer state, and if those who are looking for locations in the west would only come here they could not but be more than satisfied. The climate is charming, the soil is unsurpassed for richness & depth. It is abundantly watered. I never saw so many springs in my life as I have here or so many creeks. The latter occur from every two to six miles & as they are not bridged yet they are often dangerous even after moderate showers.

Thursday morning We were roused this morning by sad intelligence from Lawrence which as been confirmed by others who have arrived since. On yesterday morning, as stated by one of our sergeant at arms who had been out, witnessing, between 8 & 9 oclock, while the citizens of Lawrence were peacefully pursuing their different avocations or going to their work, horsemen and footmen all armed with muskets with fixed bayonets & other arms were seen collecting on Capitol Hill & the mount overlooking the town. About 11 oclock [U.S. Deputy] Marshall Donaldson [sic-Donelson] & eight men as a posse came down into the town and summoned two of their principal military men to assist them & then proceeded to make their arrest [of two free state fugitives] without the least resistance from anyone. After making the arrests they dined at the Free State Hotel after which they with their prisoners retired up to Gov Robinson’s house on the hill where the others were still stationed. About two o’clock Sheriff Jones (who they say was shot but which is doubted as all a hoax) & 18 men all on horseback came down, drew up in front of the hotel. Jones called for Gen. Samuel Pomeroy. He appeared. When Jones addressed him thus, “As one of the principal citizens of Lawrence I address myself to you. It is well known I have been repeatedly resisted in the execution of duties as Sheriff of Douglas Co. in this place & that the last time I was here an attempt was made to assassinate me. I now come to demand that all the arms, public & private, shall be brought stacked in the street & delivered to me.” And taking out his watch he said, “I give you five minutes to decide. If it is not done I will storm the town.” Pomeroy asked for a longer time. Jones said, “No, you have had five days already.” Pomeroy then consulted with the committee of safety and they determined they would deliver up the public arms consisting of a cannon & three or four howitzers. The private arms they told Jones they had no control over and he had no right to ask them. [Jones] then said he did not know as he had, but said he would pledge himself they should be returned to all who proved property. They did not give them up. To this demand he subsequently added that “they should be allowed unresistingly to destroy the two printing presses” & both to this demand & the former he added, “I demand this by order of the Court of the U.S.” Judge Lecompte is responsible, if this is true. After the cannons were delivered up, those who remained upon the hill then filed down into the town, about three hundred strong, with their cannon. [They] filed off and planted their cannon in front of the Hotel, also the cannon which had been delivered up. One portion of them went to the printing offices, took the printers prisoners, took the presses, type and all the furniture of the offices & threw them into the Kansas River, and came back whooping and screaming like savages, and parties stationed on the hills on the other side of the river answered them by whooping. They then set fire to the printing offices. Some variance of opinions occurred as to tearing down the hotel. The Georgians troops wanted to save it but the Carolinians and Missourians insisted on destroying it. They then commenced firing upon it with their cannon and platoons of musketry. Then the women & children commenced flying in every direction, some with provisions in their hands & others with some of their clothing, to the ravines & wherever they could find any security. Some were crying & asking what shall we do or where shall we go. The cannonading did not make much impression upon the walls of the Hotel & they then set fire to it. The bodies of those who had been murdered on Sunday lay in their coffins in the hotel & were burnt with it, it is supposed. Men had been sent out Tuesday to dig graves for them but were fired upon & had to quit. They then turned in and sacked all the houses, carrying off all they could find of value to them. They also set fire to Gov. Robinson’s house, and when they went away they said they would be back in the morning to finish their work. Mr. Whitman, a highly respected citizen living near Lawrence, having had a horse stolen from his claim during his absence on Monday might, went upon the hill among them to demand its return. He called for Donaldson [sic-Donelson] but was told he was busy. [Dr. John] Stringfellow then came forward & [Whitman] stated his demand to him. He promised it should be returned to him when the party who had it came in. It was the Marshall who took [the horse] from the Whitman’s claim together with saddle, bridle, & blanket. Stringfellow asked him if he thought the citizens would resist the Marshall. [Whitman] replied they would not & they never had resisted the [Marshall]’s authorities. S[tringfellow] replied they were not [Marshall’s] authorities. Mr.[Whitman] asked if they were not acting under authority of the U.S. Marshall. [Stringfellow] said yes they were, but in the enforcement of territorial law & that [the horses] were to be handed over to the Sheriff when the Marshall was done with them. While they were talking, others crowded round. One said, “Well, fighting or no fighting, we will destroy the printing presses.” Stringfellow replied to him aside, “There will be no difficulty about that.” Another said, “We’ll destroy the hotel too.” Stringfellow replied to that, [that] they were acting under law & must act accordingly, but another man he said he wished his cannon balls were larger. S[tringfellow] replied, “They are large enough. The walls are not more than a foot thick, I could break them down.” Mr. Whitman said [the Missourians] had various banners for each company but no U.S. flag. There was one he supposed was it, but when he got up close to it, it was black & white stripes without stars. Another black with a large red star in the centre. All had various mottoes upon them, one Slavery & Kansas. Mr. Townsend tells me he saw one of their men, a Missourian from Weston Mo, who said they had the hardest work to get the hotel down, that they put kegs of powder in it & couldn’t demolish it. It has just been all newly & handsomely furnished by Mr. [Shalor] Eldridge who has just come to Lawrence & was the proprietor. He had done nothing to deserve such damage to his property even from so base a government. Eldridge & his brother carried the message from the citizens to Shannon to which he & Donaldson gave the reply I formerly stated. Mr. Eldridge told him if those were the conditions he imposed he figured they must have civil war. “Well then, let us have war by God,” said Shannon. It is now ascertained a certainty that Shannon & Atchison were both with the mob on the hill & Atchison made them a speech just before they came down into the town.

This image of Lawrence, showing the demolished Free State Hotel, appeared in Harper’s Weekly, Sept. 19, 1863. (LOC Prints and Photographs Division) Every word I have written is the truth but O! it is not half the truth. I could tell the whole or begin to. I wish every man in the north could only be here & see & feel things as we do. Then they would realize how it is & not till then. Mr. Sherman says Ruffian tyranny is nothing to what the Free State people here are & have been subjected to. They would not submit to it but if they resist, the whole government from the lowest officials up to the President are against them. And [the Free State people] say even their own friends in the east will or would blame them, and so they thought they would just let the government and the Ruffians show what they would do. [Free State people] would concede all they could, to prevent it. It would make the crime of the other side the greater and the more apparent to the friends in the free states and [the free states] would then not blame them for protecting themselves. But they say if they had resisted at Lawrence just from fear of what [the Missourians] might do if permitted to come into the town, people would have said they were premature & that such a thing as their destroying as they have, never could have occurred. But now that they have shown their cloven foot, the Free State people will attack them. Mr. Whitman said the last thing he saw was the great fire and lots of blue around, which can be seen for twenty miles in some directions & which was the appointed signal for the Free State men to [take] their arms and march for Topeka, which it was understood the enemy were going to attack next. There is not a doubt entertained but what the Free State men, even with the arms they have got, will be the victors unless the others are largely reinforced from [Missouri], which they probably will be. Mr. Whitman said [the Free State men] would retake their own cannon & capture this too. Mr. Townsend says Mr. Burgess, the man from Weston, told him [the pro-slavery side] had 1400 men, & T[ownsend] strongly suspected [Burgess] was going home after more. T[ownsend] has been off through [Missouri] ever since Saturday after witnesses & he says the whole thing is strongly condemned by all the good men in the towns he was in, that it is only the vagabonds who have come over to Kansas, though some of them are men of property too. Mr. Sherman says when they get courts in which justice can be obtained, their property will have [to] pay for the damage they have been accomplices in committing. Thursday evening News has just arrived that Shannon has sent to the Fort for the U.S. troops to put down the mob, but in fact it is to protect them from the Free State men, now that he knows they have outraged law & that the F.S. men are arming for attack and resistance & would probably cut them to pieces if the troops would only stay away. O! my, my, but the Free State men are mad to fight. Companies would start from here at once if they only thought they could reach Topeka before the troops could. But the latter are so much better mounted there is no hopes of that, and their only hope now is that the Free State men already there will have cut them off before the troops come. O! how basely Gov. Shannon uses the powers invested in him by the President. He refused to call upon the station troops near Lawrence to protect it when requested by the citizens, but now when he knows they are justly exasperated at the repeated outrages upon life and property and he feels he maybe in some danger, he calls upon them. He need have no fear of personal violence for they regard him as an old imbecile who is wholly at the mercy of the mob & must act as they dictate, else his life is in danger, for they have repeatedly declared if he acted otherwise than they will have him, they will kill him. Mr. Townsend says a man in [Missouri] said that the way in which they got powers to destroy the hotel & printing presses was by representing them to the grand jury as nuisances. There is not a Free State man on the grand jury and of course they had no difficulty in getting the color of law to act under. But they had no law for burning Gov. Robinson’s house & sacking all the rest.

Tell Mary S. [that] Col. Mitchell is here & has just made a long call. He was here yesterday but I was absent. He inquired about her. If the roses & oleander are living, set the oleander where it was last year & the roses any place at all. Please tell Mary to have John clean out the cistern well & put the water pipes in again, & have the filter fixed so it will operate well if it don’t now & also to get Mr. Wm. Ilvene to whitewash. We will probably be home by the middle of June at farthest. It is very warm here for the last week although there is always a fine air blowing. I hardly expect you will read the half of this letter, it is so long. But I though perhaps Mr. M would like to hear some particulars from some one on the ground. Excuse all errors. I have written betimes & am constantly interrupted. My room has been ever since I came the public resort of all our own and all who want to talk over matters. I send this by Mr. Grogg who returns to the east. Will visit Washington & give Court information of how matters are in Kansas. After stopping in Detroit, John and Cecilia returned to Washington with the report, which ran over a thousand pages. Committee chairman William Howard presented it to the House on July 1, 1856, and after much debate, John read it to the assembly. The Congress continued to argue the Kansas question weeks past its customary recess from the sweltering heat of Washington summer, and did not finally adjourn until the end of August. John threw himself into

Postscript When they went to “hear and witness” the shocking events of 1856, John and Cecilia experienced first-hand a new culture of violence and unilateral action prevalent in the American West. Today, as America readies itself for war, I am struck by the similarities in tone between the frontier war talk of the 1850s and of today. Its origins are in the Second Amendment to the Constitution, which protected the right of Americans to form militias to keep law and order in the absence of an army. In the frontier, the paucity of courts and the ubiquity of firearms thus encouraged Americans to settle disputes themselves, without benefit of legal mediation. The historian Richard Maxwell Brown calls this extra-legal principle “no duty to retreat.” It was a departure from the medieval British common law requiring a person under threat to retreat until his back is to the wall before he could use deadly force; this would encourage people to settle quarrels in court and to protect the sanctity of human life. “No duty to retreat,” on the other hand, was best expressed by Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1953 Cold War speech: If you “meet anyone face to face with whom you disagree…and took the same risk as he did, you could get away with almost anything as long as the bullet was in front.” — that is, as long as you were the quicker draw. This was the modus operandi of the post-Civil War Western gunfighter, including Eisenhower’s avowed hero and fellow Kansan, Wild Bill Hickok, who had been an eighteen-year-old sheriff in Leavenworth in 1854, and later, a Union scout. His “walkdown” with Dave Tutt at fifty yards in 1865 in a Missouri public square epitomized the American view of murder in self-defense, in which a “true man” under threat can be acquitted for standing his ground. In Texas, where the rule was carried to its extreme, justifiable homicide extended to defense of one’s self, one’s property or even one’s values; “no duty to retreat” became known as the Texas rule in 1885. A man could fight and even pursue an adversary until the threat was over. “A man is not born to run away,” wrote Chief Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes in 1921, when he made the Texas rule federal law. Holmes had been a Union junior officer in of some of the Civil War’s bloodiest battles – Antietam, Chancellorsville, and the Wilderness among them. In the chaos of the post-Civil War West, the “good guys”—lawmen like Hickok and Wyatt Earp—represented the authority of capital: the owners of cattle ranches and mining companies and railroads, grasping for the wealth of the West, in what Brown and historian Alan Trachtenberg call the Western Civil War of Incorporation. The bad-guys were Southern-sympathizing outlaw homesteaders like Jesse James, or unaffiliated cowboys bent on mayhem and a fast buck—of the same ilk as the Border Ruffian. Our national mythology seized on the dichotomy. In foreign policy, we applied the prerogative of American police action abroad to protect corporate interests. We would stand our ground, wherever we determined we needed to. In 1947, the Truman Doctrine, intended to contain Soviet power, kept a U.S. military presence on the ground around the world, threatened war over Cuba, and sent forces to fight in Korea and Viet Nam, and countless other smaller skirmishes. The most militant impulses in American foreign policy have had their strongest advocates in Presidents from the Southwest. Now we have a Texan in the White House, proposing a war of preemption against what we fear the enemy might do—war in the subjunctive tense, typical of the spirit of “no duty to retreat.” President George W. Bush talks of terror, generalized and pervasive. “We must chose between a world of fear and a world of progress,” he told the U.N. General Assembly. That is to say, a world of orderly democracies fit for business instead of a backward, chaotic world in the thrall of outlaw, non-democratic leaders. “We are the leader,” he said, who must “combine the ability to listen to others, along with action.” This has meant arming our allies of the moment—Pakistan and Saudi Arabia, for instance—with new shipments of high-tech weapons, and threatening unilateral action as we position our troops around Iraq, our enemy of the moment. Bush argues in abstractions—freedom, terror— but his target is personal and material: the bad man who tried to kill his dad, and, incidentally, the oil reserves that bad man represents. George W. Bush and I are the same age. I am from Washington, D.C.; Bush is a Texas transplant, his family of bankers and businessmen having moved from the moneyed lawns of Greenwich, Connecticut, to the oil fields of Midland, Texas. He has called himself “a child of Vietnam,” but in fact, he and I are children of the Eisenhower era. I grew up—as I’m sure he did—cheering for the Lone Ranger on TV, and wearing my Roy Rogers cowboy boots and hat to kindergarten and brandishing my toy guns at the bad guys to be the fastest draw. So I can empathize with him when he described himself recently to Bob Woodward as a “West Texas tough guy” who wants to be seen as a liberator of the oppressed (even though this “tough guy” was a football cheerleader at Yale). It was another Texan we have to thank for the formative war of our generation. Lyndon Johnson in 1964 seized the pretext of an attack on U.S. warships on “routine patrol” in the Gulf of Tonkin to bomb North Vietnam and launch the Vietnam War. America would stand its ground and fight the expansion of communism, and Johnson did not intend to be the first President to lose a war. “Let’s hang the coonskin on the wall,” he said. But once in Vietnam, fighting a formidably determined enemy, he could not figure a way to get out without having to retreat. Americans heard and witnessed on TV the horrors of an ill-considered war on the other side of the world that was miring us in defeat. When in March of 1968, TV brought the image of Lyndon Johnson announcing that he was resigning from the presidency, I remember the shattered look on his face. His career was in ruins, his war spun out of control, his country in open rebellion. I hope George W. Bush, self-styled “child of Vietnam,” remembers that also.

Notes: 1 Childless themselves for the first years of their marriage, John and Cecilia took active interest in their many nieces and nephews. Mary Hoyt Sherman was the daughter of John’s brother Charles. In 1868, she married General Nelson A. Miles, who made his career in the West and spent much of it in Fort Leavenworth. 2 On May 24, John Brown, enraged by the sacking of Lawrence, led a posse of vigilantes consisting of five of his sons and three accomplices to murder five pro-slavery settlers in cold blood. Further reading: Brown, Richard Maxwell. NO DUTY TO RETREAT: Violence and Values in American History and Society. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992 Goodrich, Thomas. WAR TO THE KNIFE: Bleeding Kansas 1854-1861. Mechanicsburg, Pa.: Stackpole Books, 1998 ______ _______. BLOODY DAWN: The Story of the Lawrence Massacre. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University, 1991 Nichols, Alice. BLEEDING KANSAS. New York: Oxford University Press, 1954 Sherman, John. JOHN SHERMAN’S RECOLLECTIONS OF FORTY YEARS IN THE HOUSE, SENATE AND CABINET, AN AUTOBIOGRAPHY New York: The Werner Company, 1895 Smiley, Jane. THE ALL-TRUE TRAVELS AND ADVENTURES OF LIDIE NEWTON. New York: Fawcett Books, 1998 (Fiction) Stiles, T. J. JESSE JAMES: LAST REBEL OF THE CIVIL WAR. New York: Knopf, 2002 Trachtenberg, Alan. THE INCORPORATION OF AMERICA: CULTURE AND SOCIETY IN THE GILDED AGE. New York: Hill and Wang. 1982 Woodward, Bob. BUSH AT WAR. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2002

©2003 Mary-Sherman Willis. see also:

Living with Guns - An

Introduction |