|

c u r a t o r ’ s e y e |

v e r n a p o s e v e r c u r t i s |

|

Photographs often deceive us because they stand in for fact. But, ultimately, photography is an interpretive medium. A photograph works best when we accept its pretext of documentation yet acknowledge the opinion it conveys. This is similar to the written word. Through the eye, the photographed picture excites the mind in a wondrous way. It permits us, ourselves, also to form an opinion about a place in time, though we are not the photographer, who was there. If we look deeply, the photograph might strike chords in our memory. Then, we can see it metaphorically, like a poem. I have selected several contemporary landscape photographs from the immense holdings in the Library of Congress — “contemporary landscape photographs” meaning they comment upon what they behold. Two are newly acquired favorites and one is a pending acquisition. All of them share the American West as their subject. As a curator, I want to understand their commentary. I cannot resist placing them in sequence, as if they were sentences. I begin with Karen Halverson’s slant on the Sierra Nevada foothills, follow with Mark Klett’s reading of Central Arizona, and end with Edward Burtynsky’s ode to “new” California hills. Taken in this sequence, the photographs warn and inform me of what happened in the twentieth-century American environment. As in writing, the photographer makes choices, if not about form and words, then the type of camera, lens, and film. With these she emphasizes the truth of what her eye perceived — or produces distortion. Perspective, view, composition, detail, texture, quality of light, black and white or color, all are factors over which the photographer has control. Using intuition as well as conscious selection, he frames a location and commits to it with a click of the shutter. Through editing and after printing, we arrive then to contemplate the artful photographer’s vision.

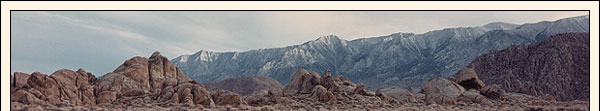

“Alabama Hills, near Lone Pine, California,” 1987 Karen Halverson, American, born 1941 Chromogenic color print Library of Congress, Prints &Photographs Division, Kent and Marcia Minichiello Collection, Library of Congress website: http://www.karenhalverson.com/ email: khalv99@yahoo.com

© Karen Halverson

Karen Halverson captured a scene in the Sierra Nevada near Lone Pine, California, in the colors of plain daylight. Some years earlier, Ansel Adams, America’s most famous photographer, felt an emotional pull to that same mountain range. He worked in black-and-white, and his choice of dramatic vistas and natural lighting allowed us to experience the awe he felt while in these mountains. Halverson wanted a clear view of the warm desert rock, soil and scrub brush. Her horizontal format elongates the range of hills, de-emphasizing the sky and expanding the landscape view. A dirt road leads our eye to the Alabama Hills, foothills of the Sierra. Swinging left from the same corner and stopping in the center of her frame, the road’s presence disturbs the continuity of Nature. More jarring yet is the battered Jeep, its doors and hatchback flung open. By being partially cut off at the bottom margin and close to us in the foreground, it seems almost capable of entering our real space. Chalky white, rectangular, the car trespasses on the soft, warm grays and blues of the flowing, organic terrain. We see what the photographer meant when she said,

But is this true: is it the car that is vulnerable in this photograph? Or is it the landscape? Acting as an anchor and adjunct to the road, the car, it seems to me, all but dominates the scene. In a place that otherwise could be timeless, its presence forces us to confront contemporary time. We are face to face with our impulse to traverse forbidding, uninhabited places. After we get there, as Halverson has, comes the realization that our presence has changed them.

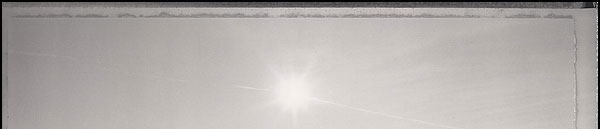

“Granite Reef Aquaduct near Mile Marker 100,” 1984 Mark Klett, American, born 1952 Gelatin silver print Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Kent and Marcia Minichiello Collection, Library of Congress Mark Klett manages this website. www.thirdview.org

© Mark Klett

Many of us experience our environment in passing, a view from a vehicle on the ground or in the air. While the square format Mark Klett has chosen approximates the experience of such a momentary look through a window, we know right away from its jagged double border that the photographer, in fact, has created a particular artifact on paper. He shows us the full image he saw, even to the edges of the separator paper of his positive-negative film. This “framing” device is intended as a conceit of the painstaking photographic process employed by the first American photographer-explorers to visit the West during the nineteenth century. These photographers prepared their heavy glass-plate negatives with wet chemicals right in the field, a tedious procedure. They had to use a commercially available solution, known as gun cotton (ordinary cotton that had been soaked in nitric and sulfuric acid, then dried), dissolve it in a mixture of alcohol and ether with potassium iodide, and pour it evenly onto the negative plate. Within seconds, they would need to sensitize the plate in a solution of silver nitrate before inserting it, while still wet, in its holder into the camera. These negatives were very much handmade. After exposure, the cameraman would retreat to his portable darkroom tent to develop the negative. Polaroid’s Type 55 sheet film makes it much easier for Klett to produce his initial negative. The sheet is actually a package, which contains the black-and-white positive, the negative, and a pod of reagent. When processing the film, which can be used as a way for the photographer to proof the image in the field, he peels apart the package and immerses the negative in a sulfite solution to fix and wash it. Choosing black-and-white, Klett also recalls the monochromatic past of photography. The film type and today’s large 4" x 5"-negative format produce sharpness, fine grain, and continuity in soft, mid-range grays. All of these enhance the reading of his Arizona subject. Klett has organized the horizon line and glistening light to force us to see the water in a canal. Though the canal appears to be far away, he makes it accessible to us by placing it dead center in his picture. The almost perfect symmetry of the composition directs our attention to the Central Arizona Project, a man-made engineering wonder fifteen years under construction to carry Colorado River water uphill to the parched south. With the sun pointing the way from above, we feel the essence of what Klett saw without the need for words: Man has been playing God in this place.

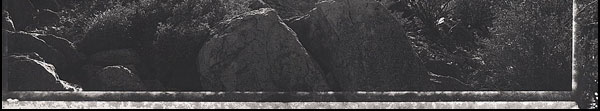

“Oxford Tire Pile #5, Westley, California,” 1999 Edward Burtynsky, Canadian, born 1955 Chromogenic color print Courtesy of Charles Cowles Gallery www.cowlesgallery.com, New York; email: info@cowlesgallery.com. Burtynsky’s website: www.edwardburtynsky.com

© Edward Burtynsky

Edward Burtynsky has put Westley, California, another place where humans have been at work, in his sights. Here the flat earth of a canyon in the California coastal range gives way in the foreground to the donut-shaped forms rampaging in piles of circles and ellipses as far as we can see. To the left is a big mountain of countless piled tires, parting in the center of the photograph. To the right, we make out Nature’s shapely contour beginning to be transformed by a consuming swarm of more tires. They seem out of control. They may be taking over. What we can’t see in this view is the fire in an adjacent recycling dump, brought on by Nature during an electrical storm and burning out of control as it pollutes air, soil, and groundwater. Because it was an environmental disaster waiting to happen, the State of California has since ordered Oxford Tire Recycling to clean up the 40-acre mountain of seven million tires, which had been accumulated since the 1960s and was one of the world’s largest tire piles. The scene Edward Burtynsky witnessed no longer exists.

Verna Posever Curtis is a curator of photography in the Prints & Photographs Division at the Library of Congress. The recently acquired Kent and Marcia Minichiello Collection of environmental landscape photography in the Library of Congress, which includes Halverson’s and Klett’s photographs, was a gift to the nation on the occasion of the Library’s Bicentennial celebration.

|

©2003 Library of Congress